CONSUMER SPENDING IS a matter of confidence, and declining retail sales can often be one of the first barometers of economic sentiment. The trend we have seen since early in the year has been further backed up by the economic news which, despite positive reporting from many listed companies, has brought a storm cloud of negative sentiment.

Fears of rising interest rates, even though they may have been slow to happen, will dampen consumer spending. The threat of trade wars with China and an increased cost of imports and reduced income from exports are playing on investors’ mind. We’ve seen a drop in the Dow Jones reflect this fall in confidence, and it seems likely that there will be some further belt-tightening going on in the foreseeable future.

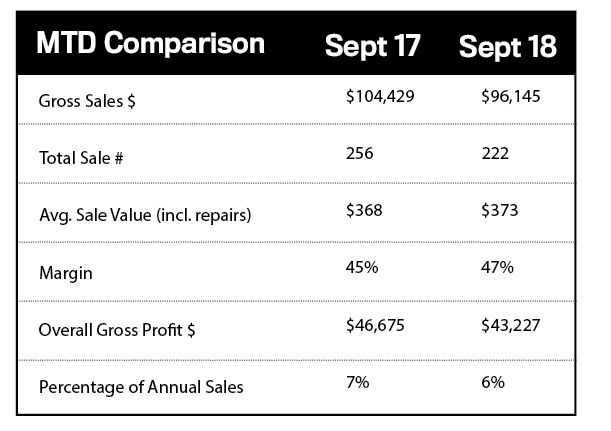

Below is a comparison of the individual monthly data for September versus the same month last year.

Our same-store September data year-to-date showed a decline of 0.52 percent in the rolling 12-month sales figure compared to September 2018. Average store sales for the 12-month period to September was $1,579,921, down from $1,588,204 at the end of August. This has extended our run of declining sales to eight months when our rolling 12-month sales stood at $1,629,755.

So what’s caused this to happen? Ever since the financial crisis in 2008, governments all around the world have increased the amount of money that is in circulation. Their logic? That more money encourages more spending.

Advertisement

To a large extent their strategy has worked, as if you hand out cash to the “man in the street” he will naturally spend it. Now you might be wondering how this works. Governments don’t appoint cash dealers to stand on street corners doling out dollar bills. They will generally do it through the banking system in one of two ways. The first is to print money, either figuratively or literally. These days most money travels electronically, so it usually consists of blips on a screen. This money is made available to banks to lend as mortgages or credit card debt – which allows it to filter its way through to consumers. The other way they can do it is through debt – treasury bills and government bonds can be issued to finance the government deficits that are increasingly the norm for most countries. These are effectively a demand on the government to repay later. These debts are viewed as ironclad, as a government is always able to guarantee its payments (by printing more money, but this can cause its own problems as you will see!) So the government can control the money in circulation by selling more bonds (which takes money out of the system) or buying back their bonds (by putting more money into the system re-purchasing the bonds).

Now this all sounds pretty simple, but it can come at a price. Printing money can cause the value of a currency to decline (like any rule of supply and demand, the more of something there is the less anyone will pay for it). A declining dollar can make exports more competitive, but it does raise the cost of importing goods because you will need more dollars to buy the foreign product so this will lower demand for goods. Creating more government debt can be a way of mopping up the money, but it can lead to higher interest rates as lenders get more nervous the higher debt you have (even for governments) which is happening now.

There is a lot of debt, both personal and government, that is sloshing around the world. Personal debt is high because of all the money that the governments have injected in the economy through the banks.

Now that the government is tightening the money supply, there is a nervousness that many of those with high borrowings won’t be able to deal with the increase of interest rates that will now happen as money becomes tight again. The fiscal stimulus of money being injected into the economy may have kicked the can down the road, but to throw in another cliché, the chickens may be about to come home to roost.