Author Jennifer Heebner (top right) with the group from the Women’s Jewelry Association New York Metro chapter in front a pool of water inside the mine. It’s mountain water, but abandoned equipment in the mine leached unhealthy elements into it. Nobody took a dip or a sip.

I THOUGHT OLGA GONZALEZ was joking when she texted me that her Gem-A instructor “always dreamed of going to New Jersey” to see minerals.

You go to New Jersey to reach “the shore” (as Philadelphians call the southern state beaches) or to drive through the state to get to New York City. Why else go there, thought this lifelong Pennsylvania resident? Turns out there’s an incredible geologically related reason to visit.

“New Jersey is special in the mineral world,” explained Gonzalez, a certified gemologist (FGA DGA) from Gem-A, seasoned public relations professional, and the president of the Metropolitan chapter of the Women’s Jewelry Association (WJA). “My professor told me he always dreamed of going to N.J. to see the minerals in Ogdensburg.”

Advertisement

These N.J. minerals—357 in total, with 28 that are found only in this place on earth—are located on the site of the Sterling Hill Mining Museum and now closed zinc mine. Located in Ogdensburg, groups can tour the mine and the museum, the latter of which is full of quirky remnants of the site’s past as well as fossils, gems, and fluorescing stones.

Given the journey from New York City is just two hours, Gonzalez arranged for a chapter field trip in mid-May. After years of dissing my state neighbor, I figured I owed it the respect to attend.

It’s me—author Jennifer Heebner, readjusting my eyes to the light.

Destination: Ogdensburg

I left the Philly burbs early on a Saturday to drive north. Google Maps directed me to take local roads (not the Turnpike) flanked by lush lawns and trees. It was a precursor to more of the same once I arrived; hilly vistas and quiet streets greeted me at the Sterling Hill entrance. This wasn’t the New Jersey I knew.

Nine others from WJA (I’m a member and former Metropolitan chapter president) were present, including President-Elect Elyssa Jenkins-Perez from the Jewelers Vigilance Committee and Communications Co-Vice President Jenith Gomez of Hamilton Jewelers. Dominic Zampella, a retired local middle school science teacher, was our guide for the day, along with a guide-in-training named Lewis.

Our first stop was Zobel Hall, now the Sterling Hill Mining Museum, which previously served as a change house.

Hanging baskets for miners to dry damp uniforms overnight

Museum Finds

Built in the 1930s, Zobel Hall houses lockers, showers, and wire baskets—one for every miner—hanging from the ceiling. Miners would hang their damp uniforms to dry overnight. In the mine’s heyday, 300 lockers filled the room, though just a handful now remain.

The rest of the space is filled with 12,000 oddball artifacts. Among them are industrial drill bits (as big as shotguns) used in the mine, ore specimens, a 10-foot-long periodic table of the elements with cubbyholes for samples, and a mineral gallery donated by the Oreck family—think vacuums.

Relics of the past abandoned inside the mine. Those shotgun-looking things are the industrial drill bits that created all the tunnels.

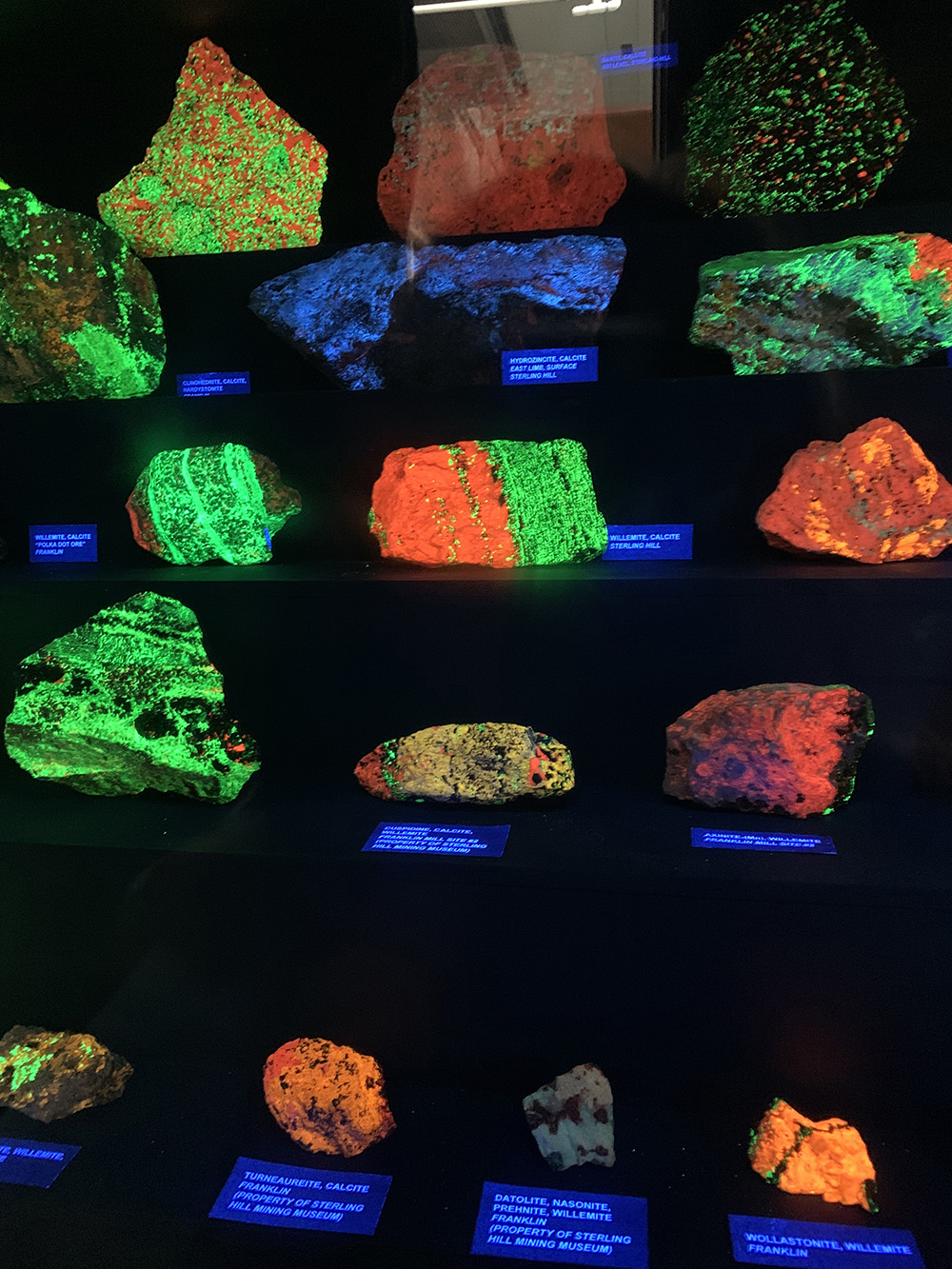

Specimens from all over the world are housed in glass display cases that sit opposite the old showers. The display is impressive and includes a wide variety of rocks—from fluorite found in Tennessee to Peruvian pyrite. Footprints from dinosaurs—called ichnites—that once roamed the state were another highlight, as was a darkened, enclosed corner containing specimens that fluoresced under ultraviolet light.

All the fluorescent rocks were found nearby. The display was so robust that it’s not too surprising that the immediate area regards itself as the “Fluorescent Mineral Capital of the World.” There are even more specimens—700-plus—in another museum adjacent the mine, where we headed next.

A massive gem collection donated by the Oreck family of vacuum fame.

Into the Mine

Access to the mine, which closed in 1986 for financial reasons, is by walking into the side of the Sterling Hill Mountain. Zampella led us in via the adit level—a horizontal, first-floor mine entrance that gave way to a long dimly lit tunnel. It is one of over 35 miles of stone passageways inside the mine, which is 56 degrees year-round. This is the only level visitors see, though 24 others exist. “The mine extends down 2,550 feet, or the length of two Empire State buildings,” he explains.

One of many long (and creepy) tunnels in the mine. There are 35 miles of them.

The mine opened in 1850, though Dutch settlers in the 1600s scoured the area for what they thought was iron ore. Once known that the area was rich in zinc, which prevents steel from rusting and is a key component in metal products like brass, entrepreneurial minds sourced what they could.

While operational, the mine saw 11 million tons of ore extracted. The ore contains three main minerals—franklinite, which is unique to the locality of Franklin, N.J.; willemite (rare but found in abundance in the area); and zincite, which is extremely rare to find in its mineral state anywhere. All these deposits were born on the bottom of a shallow sea that existed 1.3 billion years ago and “changed into these metamorphic rocks,” explained Zampella.

Relics from the past remain at the mine as equipment was abandoned upon closure. Items include more massive drill bits (one that’s rumored to have dug the Lincoln Tunnel), bells for communication, ore cars, lights, and ladders, giving guests a peek at the hard work that once occurred.

The toilets—a seat over a metal bucket that was emptied once weekly—also remained. Yuck. Misfit miners in trouble with their boss had that unpleasant task.

Advertisement

Leaving the Luminescence

We left the tunnels to finish the tour in the Thomas S. Warren Museum of Fluorescence. It’s full of luminescent specimens as neon as 1980s fashion. It was remarkable to see so many and realize the importance of this part of the world for fans. Fifteen percent of roughly 5,000 mineral species are known to fluoresce under ultraviolet light, and Sterling Hill and nearby Franklin are home to 88 of them! In fact, collectors can pay $5 plus $1.50 per pound to pick samples from outside. To find the ones that fluoresce, rockhounds bring a blanket and a flashlight, viewing potential treasures under cover to see what lights up.

A sampling of the fluorescent mineral specimens that are in the museum (more are in another part of the complex)

And did you know that part of the film Zoolander was shot in the mine? Ben Stiller’s Derek Zoolander character returned home to purportedly mine coal, and that scene was filmed at Sterling Hill.

New Jersey, you did not disappoint. My apologies for past impressions; I had no idea what a treasure trove of mineral richness you had.

PHOTO GALLERY (21 IMAGES)